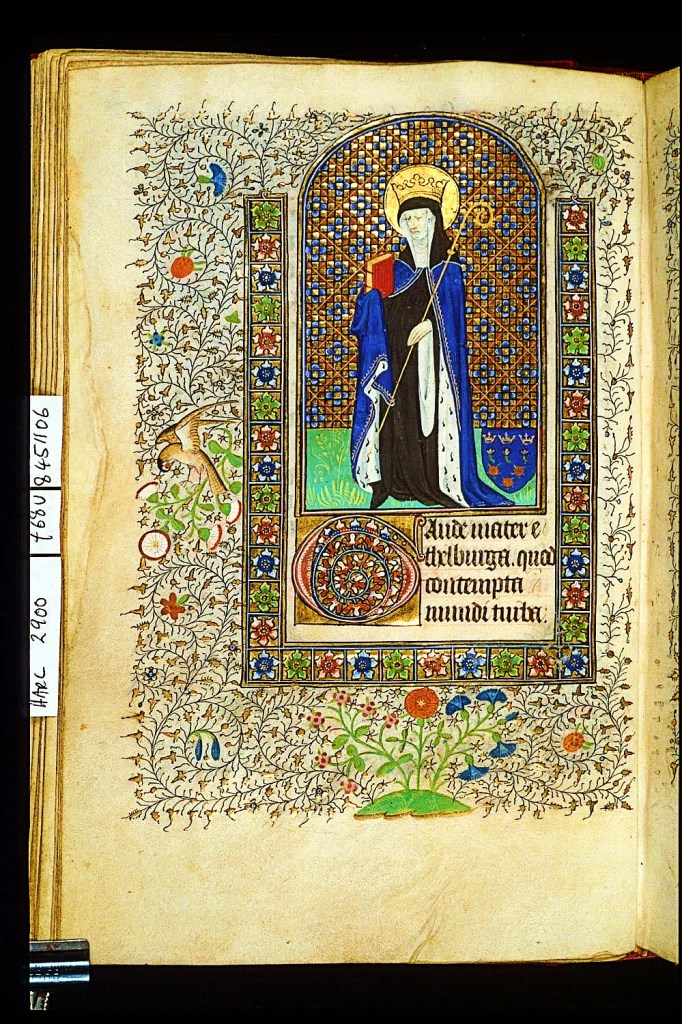

Saint of the Day – 11 October – Saint Ethelburga of Barking (Died c782) Virgin, First Abbess of the double Monastery (for men and women) at Barking, in Essex, England, founded by her brother, Miracle-worker. Sister of St Erconwald of London (Died c 693, Bishop of London and known as “The Light of London.” Ethelburga is one of a significant number of female religious leaders who played an important role in the first Century of the Anglo-Saxon Church. Also known as – Adilburga, Æthelburh, Edilburge, Etelburg, Ethelburgh. Ethelburge. Additional Memorial – 12 October in the Diocese of Brentwood of which Barking forms a part

Not much is known about the family origin of these two saintly siblings but their names suggest they might have been connected to the Kentish Royal family. The main source for Ethelburga’s life is St Bede’s Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum which recounts the foundation of Barking Monastery, early miracles there and Ethelburga’s death. St Bede describes Ethelburga as “upright in life and constantly planning for the needs of her community.”

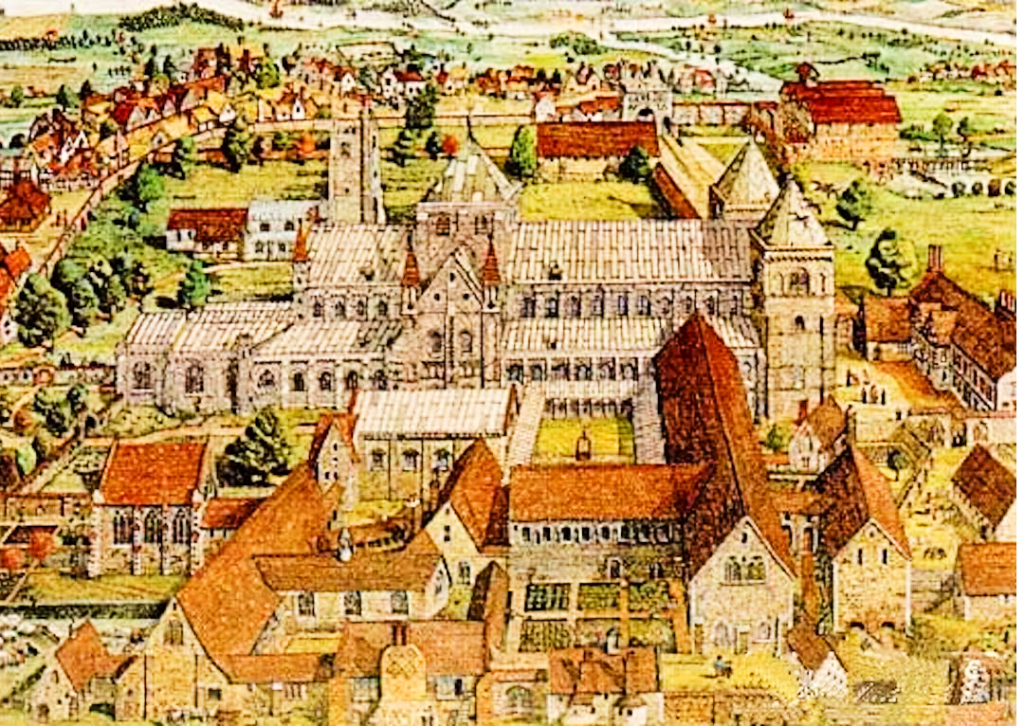

Some time before he became the Bishop of London in 675, Erconwald founded a double Monastery at Barking for his sister and a Monastery at Chertsey for himself. Barking appears to have already been established by the time of the plague in 664.

Around the same year, 675, Ethelburga founded the Church of All Hallows Berkyngechirche (now known as All Hallows Barking or All Hallows by the Tower) in the City of London on land given to her by her brother.

St Bede writes:

“In this Convent many proofs of holiness were effected which many people have recorded, from the testimony of eyewitnesses, in order that the memory of them might edify future generations. I have, therefore, been careful to include some in this history of the Church …

When Ethelburga, the devout Mother of this God-fearing community, was herself about to be taken out of this world, one of the sisters, whose name was Tortgyth, saw a wonderful vision. This nun had lived for many years in the Convent, humbly and sincerely striving to serve God and had helped the Mother to maintain the regular observances, by instructing and correcting the younger sisters.

In order that Ethelburga’s strength might be ‘made perfect in weakness’ as the Apostle says, she was suddenly attacked by a serious disease. Under the good Providence of our Redeemer, this caused her great distress for nine years, in order that any traces of sin which remained among her virtues, through ignorance, or neglec,t might be burned away, in the fires of prolonged suffering.

Leaving her cell one night at first light of dawn, this Sister saw distinctly, what appeared to be a human body wrapped in a shroud and shining more brightly than the sun. This was raised up and carried out of the house where the Sisters used to sleep. She observed closely to see how this appearance of a shining body was being raised and saw, what appeared to be cords, brighter than gold which drew it upwards until it entered the open heavens and she could see it no longer. When she thought about this vision, there remained no doubt in her mind that some member of the Community was shortly to die and that her soul would be drawn up to Heaven by her good deeds as though by golden cords. And so it proved not many days later, when God’s beloved Ethelburga, the Mother of the Community, was set free from her bodily prison. And none, who knew her holy life, can doubt that when she departed this life, the gates of our heavenly home opened at her coming.

In the same convent there was also a Nun of noble family in the world, who was yet more noble in her love for the world to come. For many years she had been so crippled that she could not move a single limb and hearing that the venerable Abbess’ body had been carried into the Church until its burial, she asked to be carried there, and to be bowed towards it, in an attitude of prayer. Then she spoke to Ethelburga as though she were still alive and begged her to pray to God on her behalf and ask Him of His mercy to release her from her continual pain. Her request received a swift reply; for twelve days later she was set free from the body and exchanged her earthly troubles for a heavenly reward.

Three years after the death of the Abbess, Christ’s servant Tortgyth, was so wasted away by disease … that her bones scarcely held together, until finally, as death drew near, she lost the use of her limbs and even of her tongue. After three days and nights in this condition, she was suddenly refreshed by a vision from Heaven, opened her eyes and spoke. Looking up to Heaven, she began to address the vision …: “I am so glad that you have come; you are most welcome.” She then remained silent for a while, as if awaiting an answer from the person whom she saw and spoke to; then, seeming a little displeased, she said, “This is not happy news.” After another interval of silence, she spoke a third time: “If it cannot be today, I beg that it may not be long delayed.” Then she kept silent a little while as before and ended: “If this decision is final and unalterable, I implore that it may not be delayed beyond the coming night.” When she had finished, those around her asked her to whom she had spoken. “To my dearest Mother Ethelburga,” she replied and, from this they understood that she had come to announce the hour of her passing was near. So after a day and a night her prayers were answered and she was delivered from the burden of the body and entered the joys of eternal salvation.”

Several more miracles are also recorded, relating to an outbreak of plague in the community. In Ethelburga’s time, Barking Abbey was a double Monastery as was common in the earlier Anglo-Saxon period but it’s the bonds of community and affection between Ethelburga and her Nuns which emerge most memorably from St Bede’s account – ‘golden cords’ of another kind than those Tortgyth saw in her vision.

Barking Abbey grew to be one of the most important Monasteries in the country and, at the time of the Dissolution, it was the third richest in England. It was closely associated with a number of powerful Royal and noble women, including the wives and sisters of Kings – and, even St Thomas à Becket’s sister. The Abbess of Barking was not only an important landowner but a baroness in her own right, required to supply the king with soldiers in wartime like any secular lord. Barking also had a strong literary and educational tradition which continued throughout the medieval period- learned authors such as St Aldhelm (in the 8th Century) and Goscelin (in the 11th) wrote Latin works for the Nuns of Barking and several Nuns composed their own poetry and prose. Perhaps the first female author from England whom we can name was Clemence of Barking Abbey, who wrote a Life of St Catherine in Anglo-Norman, in the twelfth Century; a Nun of Barking (either Clemence or someone else) also wrote a Life of St Edward the Confessor, around the same time. Barking Abbey has been described as “perhaps the longest-lived, albeit not continuously recorded, institutional centre of literary culture for women in British history.” And it all began with our Saint Ethelburga.

Ethelburga was buried at Barking Abbey. The Old English Martyrology records her Feast day as 11 October. There are many Churches across England dedicated to St Ethelburga and many regions, streets, estates, schools and institutions too.

St Eerconwald HERE:

https://anastpaul.com/2020/04/30/saint-of-the-day-30-april-saint-erconwald-of-london-died-c-693-the-light-of-london/

2 thoughts on “Saint of the Day – 11 October – Saint Ethelburga of Barking (Died c782) Virgin, Abbess”