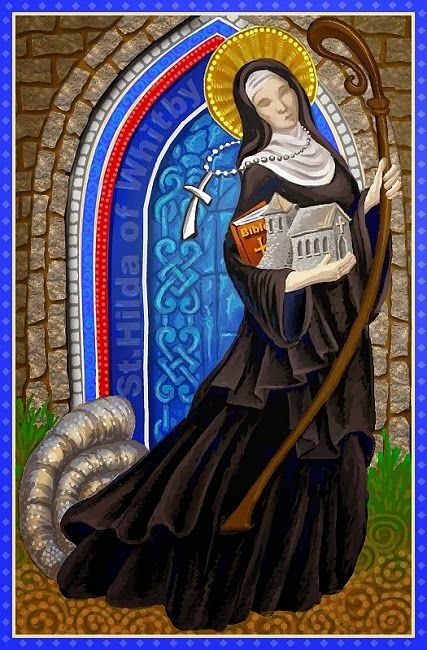

Saint of the Day – 17 November – Saint Hilda of Whitby (c 614–680) Abbess, Apostle of Charity, teacher, administrator and advisor, spiritual director, reformer – born in c 614 at Northumbria, England and died in 680 of natural causes – also known as St Hild. St Hilda was the founding abbess of the monastery at Whitby, which was chosen as the venue for the Synod of Whitby. An important figure in the Christianisation of Anglo-Saxon England, she was abbess at several monasteries and recognised for the wisdom that drew kings to her for advice. Patronages – learning and culture, poetry.

The source of information about Hilda is the Ecclesiastical History of the English People by St Bede the Venerable (673-735) Doctor of the Church, in 731, who was born approximately eight years before her death. He documented much of the Christian conversion of the Anglo-Saxons.

According to Bede, Hilda was born in 614 into the Deiran royal household. She was the second daughter of Hereric, nephew of Edwin, King of Deira and his wife, Breguswīþ. When Hilda was still an infant, her father was poisoned while in exile at the court of the Brittonic king of Elmet in what is now West Yorkshire. In 616, Edwin killed Aethefrith, the son of Æthelric of Bernicia, in battle. He created the Kingdom of Northumbria and took its throne. Hilda was brought up at King Edwin’s court.

In 625, the widowed Edwin married the Christian princess Æthelburh of Kent, daughter of King Æthelberht of Kent and the Merovingian princess Bertha of Kent. As part of the marriage contract, Aethelburh was allowed to continue her Roman Christian worship and was accompanied to Northumbria with her chaplain, St Paulinus of York, a Roman monk sent to England in 601 to assist Augustine of Canterbury. Augustine’s mission in England was based in Kent and is referred to as the Gregorian mission after the pope who sent him. As queen, Æthelburh continued to practice her Christianity and no doubt influenced her husband’s thinking as her mother Bertha had influenced her father.

In 627 King Edwin was Baptised on Easter Day, 12 April, along with his entire court, which included the 13-year-old Hilda, in a small wooden church hastily constructed for the occasion near the site of the present York Minster.

In 633 Northumbria was overrun by the neighbouring pagan King of Mercia, at which time King Edwin fell in battle. St Paulinus accompanied Hilda and Queen Æthelburh and her companions to the Queen’s home in Kent. Queen Æthelburh founded a convent at Lyminge and it is assumed that Hilda remained with the Queen-Abbess.

Hilda’s elder sister, Hereswith, married Ethelric, brother of King Anna of East Anglia, who with all of his daughters became renowned for their Christian virtues. Later, Hereswith became a nun at Chelles Abbey in Gaul (modern France). Bede resumes Hilda’s story at a point when she was about to join her widowed sister at Chelles Abbey. At the age of 33, Hilda decided instead to answer the call of Bishop St Aidan of Lindisfarne and returned to Northumbria to live as a nun.

Hilda’s original convent is not known except that it was on the north bank of the River Wear. Here, with a few companions, she learned the traditions of Celtic monasticism, which Bishop Aidan brought from Iona. After a year Aidan appointed Hilda as the second Abbess of Hartlepool Abbey. No trace remains of this abbey but its monastic cemetery has been found near the present St Hilda’s Church, Hartlepool.

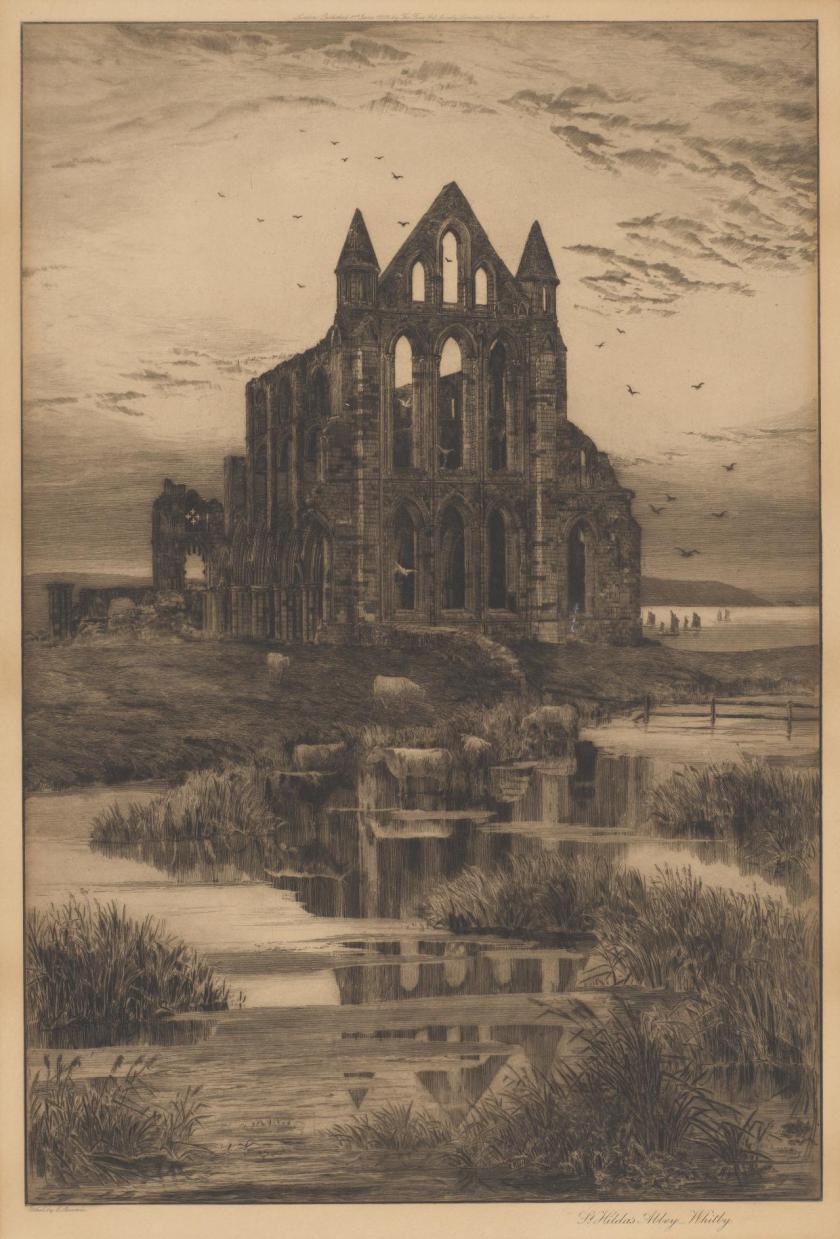

In 657 Hilda became the founding abbess of Whitby Abbey, then known as Streoneshalh, she remained there until her death. Archaeological evidence shows that her monastery was in the Celtic style, with its members living in small houses, each for two or three people. The tradition in double monasteries, such as Hartlepool and Whitby, was that men and women lived separately but worshipped together in church. The exact location and size of the church associated with this monastery is unknown.

Bede states that the original ideals of monasticism were maintained strictly in Hilda’s abbey. All property and goods were held in common, Christian virtues were exercised, especially peace and charity. Everyone had to study the Bible and do good works.

Five men from this monastery later became bishops. Two, John of Beverley, Bishop of Hexham and Wilfrid, Bishop of York, were Canonised for their service to the Church at a critical period in its fight against paganism.

Bede describes Hilda as a woman of great energy, who was a skilled administrator and teacher. As a landowner she had many in her employ to care for sheep and cattle, farmin, and woodcutting. She gained such a reputation for wisdom that kings and princes sought her advice. However, she also had a concern for ordinary folk such as St Cædmon (memorial 11 February). He was a herder at the monastery, who was inspired in a dream to sing verses in praise of God. Hilda recognised his gift and encouraged him to develop it. Bede writes, “All who knew her called her mother because of her outstanding devotion and grace”. Read St Caedmon’s beautiful story and Hymn here: https://anastpaul.com/2019/02/11/saint-of-the-day-11-february-st-caedmon-died-c-680/

The prestige of Whitby is reflected in the fact that King Oswiu of Northumberland chose Hilda’s monastery as the venue for the Synod of Whitby, the first synod of the Church in his kingdom. He invited churchmen from as far away as Wessex to attend the synod. Most of those present, including Hilda, accepted the King’s decision to adopt the method of calculating Easter currently used in Rome, establishing Roman practice as the norm in Northumbria. The monks from Lindisfarne, who would not accept this, withdrew to Iona and later to Ireland.

Hilda suffered from a fever for the last seven years of her life but she continued to work until her death on 17 November 680, at what was then the advanced age of sixty-six. In her last year she set up another monastery, fourteen miles from Whitby, at Hackness. She died after receiving viaticum and her legend holds that at the moment of her death the bells of the monastery of Hackness tolled. A nun there named Begu claimed to have witnessed Hilda’s soul being borne to heaven by angels.

A local legend says that when sea birds fly over the abbey they dip their wings in honour of Saint Hilda. Another legend tells of a plague of snakes which Hilda turned to stone, supposedly explaining the presence of ammonite fossils on the shore; heads were carved onto these ‘petrified snakes’ to honour this legend. In fact, the ammonite genus Hildoceras takes its scientific name from St Hilda. It was not unknown for local “artisans” to carve snakes’ heads onto ammonites and sell these “relics” as proof of her miracle. The coat of arms of nearby Whitby includes three such ‘snakestones’ and depictions of ammonites appear in the shield of the University of Durham’s College of St Hild and St Bede. A carved ammonite stone is set into the wall by the entrance to the former chapel of St Hild’s College, Durham, which later became part of the College of St Hild and St Bede.

St Hilda was never formally Canonised as her life is pre-congregation but the veneration of St Hilda from an early period is attested by the inclusion of her name in the calendar of St Willibrord, written at the beginning of the 8th century. According to one tradition, her relics were translated to Glastonbury by King Edmund, another tradition holds that St Edmund brought her relics to Gloucester.

Thank you for letting us know about this saint Hilda. And thanks also to saint Bede for first-hand information about her. I must confess that November 17 was for me, until now, the feast day of saint Elizabeth of Hungary, patron saint of the Franciscan Third-Order (along with saint Louis of France).

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am happy you enjoyed her story. Last year I did St Elizabeth, who is one of my favourites – we have a beautiful stained glass of her in our Cathedral – so toda,y I focused on one of these little- known Saints.

LikeLike

I wonder if you could help me please. I have a woodcut of the Whitby Abbey picture and am trying to find out the name of the artist. He has signed it but am finding it difficult to decipher. I’ve tried to read the signature from your picture, but am unable to zoom it large enough. Can you please have a look and see if you have better luck than us, or alternatively, can you let me know where you found the picture (if, of course, it does not belong to you). Kind regards, Anne White

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi there Anne – let me get over Easter and I will certainly try. I will comment back here next week.

Blessed Easter wishes!

LikeLike

Hi again Anne – I am afraid I have not been more successful than yourself in deciphering the signature. It us a free domain find on Google. Perhaps you could try on Wikipedia Commons? Apoloigies, please let me know if you find it. 🙏

LikeLike